If you’ve ever seen the claim that Shakespeare “invented” 1,700 English words, you’ve probably paused mid-scroll and thought, huh, that’s a lot. For most of us, pop culture pushes that figure like gospel truth.

But peel back the layers, and you uncover a story that’s richer, a bit messy, and far more interesting than that tidy headline.

Here’s a look at what that “1,700” really means – and why Shakespeare’s real linguistic legacy is even more fascinating.

Key Highlights

- Shakespeare is the first recorded source for hundreds of words, not a fixed 1,700.

- Many “Shakespeare words” were antedated but he popularized countless expressions.

- His creativity showed in affixation, conversion, and new compounds.

- Hundreds of his words like lonely, fashionable, and eyeball are still used today.

The Headline Number, Then the Real Story

You’ll often spot long lists online – columns of words allegedly coined by Shakespeare. The Oxford English Dictionary, or OED, is usually what fuels those numbers.

What matters is to grasp what the OED actually tracks: the earliest written instance it has for a word or a meaning, not necessarily who first thought it up. Think about how printed records worked back in sixteenth-century England.

Most ordinary folks didn’t write much, and few works survived – or got printed – except those that became plays or prominent literature. Shakespeare’s plays got printed, reprinted, studied ,and reprinted some more.

That means the OED often cites Shakespeare as its “first recorded” usage simply because his writing survived. And that often leads people to equate “first recorded” with “invented.”

Not quite fair to the man – or the record-keeping, for that matter. What makes this more interesting is how OED entries aren’t set in stone. Lexicographers keep revising entries when they uncover earlier examples – even after they’d credited Shakespeare.

That process, called “antedating,” shrinks or reshapes his lexicographic footprint over time. Charlotte Brewer, a Shakespeare-and-OED specialist, documents how many of his credited “firsts” shift into earlier citations when new evidence surfaces.

Real Counts from Trustworthy Sources

Time to get into some numbers based on reliable research. One resource, from the University of Oxford, combed through OED quotations and reports that Shakespeare has roughly 33,300 total citations, and just over 2,000 that are tagged as “first quotations,” where his writing is the earliest instance the dictionary has recorded.

Then there’s a University of Melbourne overview that’s been quoted widely in major media. It adds nuance: Shakespeare appears as the first recorded writer for about 1,500 words, and about 7,500 meanings or senses of words.

What throws people is, “those figures vary.” Why? Because the OED entries continue getting revised as new evidence shows up.

So that often-repeated “1,700 words” is shorthand for a moving target; it bundles together words and senses that the OED currently credits to Shakespeare. It doesn’t mean he invented every one of them in real life.

Why “First Recorded Use” Isn’t the Same as “Invention”

Two big ideas help you separate myth from method:

Printed evidence skews the record

Shakespeare enjoyed wide printing and preservation. The OED can only cite what’s in writing.

So a playwright whose work gets printed dozens of times naturally ends up with a disproportionate share of “first recorded” tags – even if friends or lesser-known writers were saying the same things at the same time.

Antedatings are common

As scholars dig through archives, they unearth earlier usages. Brewer and others show that hundreds of Shakespeare-first items have been antedated, shrinking his official tally over time.

It’s nobody’s fault – just the truth about how dictionaries evolve. Merriam-Webster, among other reputable lexicographers, cautions against sweeping claims.

Frequently touted words or phrases credited to Shakespeare turn up in earlier sources, or in different senses. Bottom line? He didn’t literally “invent” all these words – but his usage did help spread them.

So, How Many “New” Words Did He Actually Give Us?

If “new” means “first recorded in writing and surviving today,” the safest answer is: hundreds, not thousands. And that number isn’t fixed – dictionary entries shift over time.

But if you broaden “new” to include “first recorded sense of an existing word,” then you’re talking thousands. That speaks volumes.

Context matters: Early Modern English was a bubbling pool of linguistic creativity – estimates range from 10,000 to 25,000 new words entering the language in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Shakespeare worked right in that frenzy – and the stage let his wordplay launch into the public consciousness.

Patterns of Shakespeare’s Word-Making

- Affixation: You can spot this when he adds prefixes or suffixes to existing words – think “un-” plus a base or agentive “-er.” “Swaggerer” or playful un-formations are good examples.

- Conversion: That’s turning one part of speech into another – like noun → verb or vice versa – without adding anything. Classic instance: “grace” as a verb.

- Compounding and set phrases: He strings words together into new compounds or idioms – think “faire-play” and “pell-mell.” Drama made those swim into public usage.

It’s less about lone invention and more about highly visible, theatrical coinage that stuck.

Examples of Words First Recorded in Shakespeare That We Still Use

Here’s a handy sample. These are words – or senses of words – that OED currently credits to Shakespeare’s first recording, and which remain in everyday usage today. All grounded in solid OED-based lists and academic summaries.

| Word | Work & Date | OED Note | Still Common Today? |

| fashionable | Troilus and Cressida (1602-03) | First recorded by Shakespeare, followed soon | Yes – used in fashion trends |

| eventful | As You Like It (1599-1600) | First recorded in Shakespeare | Yes – even in headlines |

| fitful | Macbeth (1606) | First recorded in Shakespeare | Yes – regular descriptive adjective |

| frugal | Merry Wives of Windsor (1597) | First recorded for sense, other senses later | Yes – common in finance/lifestyle |

| eyeball | Rape of Lucrece (1594) | First recorded for “whole eye” sense; another sense from 1575 | Yes – everyday anatomical term |

| fixture | Merry Wives of Windsor (1597) | First recorded in Shakespeare | Yes – in real estate, sports |

| fortune-teller | Comedy of Errors (1592-94) | First recorded here | Yes – used both literally & figuratively |

| flawed | King Lear (1605-08) | First recorded here | Yes – common in reviews |

| full circle (adv.) | King Lear (1605-08) | First adverbial use recorded | Yes – common phrase |

| fairyland | Midsummer Night’s Dream (1594-95) | First recorded here | Yes – fantasy term still used |

| zany | Love’s Labour’s Lost (1593-95) | Early Shakespeare use; widely used later | Yes – casual adjective |

| auspicious | The Tempest (1610-11) | First recorded for specific sense | Yes – formal adjective |

| bare-faced | Midsummer Night’s Dream (1594-95) | First recorded in “face uncovered” sense | Yes – e.g. “bare-faced lie” |

| lonely | (pre-1616) | OED’s earliest evidence in Shakespeare | Yes – extremely common adjective |

Take “assassination,” for example – Macbeth uses it. You’ll see that hailed everywhere. But scholars have antedated it to the 1570s. Perfect highlight of how our “first-recorded” claims shift as new sources pop up.

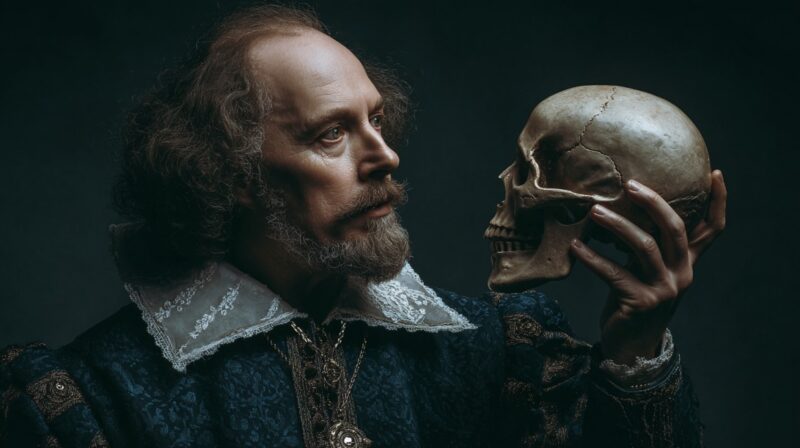

What About All Those Famous Phrases?

You know the ones – “break the ice,” “wild-goose chase,” “wear your heart on your sleeve.” Posters and T-shirts love crediting Shakespeare for dozens of idioms. Sometimes that’s accurate.

Libraries like the Library of Congress have traced earlier versions for “fair play,” “hoodwinked,” and “tongue-tied.” That said, Shakespeare did spread many of those expressions via plays that became wildly popular.

Writers and advertisers aren’t lying – they just sometimes shortcut nuance. He didn’t always invent the phrase, but he often popularized it during a moment when printing and performance made wide audience exposure possible.

Why Shakespeare’s Totals Are So High in the OED

- Top-quoted author: OED editors leaned heavily on his works during the dictionary’s compilation. That sheer volume means he naturally dominates first-citation counts – roughly 33,300 total quotations, including over 2,000 “first quotations” – per Oxford research.

- Printed words last longer: Everyday speech didn’t leave as many print traces, especially from women or regional sources. Printed drama stuck. Scholars like Brewer note the print-based bias that gives print-preserved writers a louder lexicographic voice.

It’s not a question of favoritism, but of what survives in the record.

Reality-Check on Viral Lists

Internet lists of “Shakespeare inventions” go viral fast. But dictionary editors regularly caution that many claimed examples were recorded earlier in other sources, or involve senses that shifted in meaning.

That doesn’t flatten Shakespeare’s imprint; it adds nuance. His work rode the wave of word borrowing and experimentation.

Words such as “laughable,” “eventful,” “accommodation,” and “lack-lustre” traveled widely after he put them into play, and the Folger highlights how they helped prime the language.

How Scholars Judge Whether a “Shakespeare Word” Still Exists

Researchers aren’t guessing when they say a word “survives.”

- Whether the OED marks the headword and sense as current rather than outdated or archaic.

- Usage in modern writing – journalism, academic texts, everyday corpora.

- Whether, even after antedatings, Shakespeare’s citation remained a key early example.

- Brewer’s catalogues, which categorize words that are “only in Shakespeare,” those adopted by others, and those that have been antedated since 2000.

That gives robust backing to claims about which words continue to thrive in modern English.

Practical Tips for Teachers, Writers, Curious Readers

- Be precise with language: Say “first recorded in Shakespeare” or “OED’s earliest evidence appears in Shakespeare.” That’s accurate without the “he invented” overclaim.

- Treat the numbers as fluid: Think in terms of “hundreds of headwords, thousands of senses” rather than a fixed number.

- Use clear, documented examples: That sample word table above is solid – OED-based, clear, and shows today’s usage.

- Make word formation visible in class: Shakespeare’s affixation, conversion, and compounding are tangible and fun to explore. Folger’s teaching materials are solid at introducing that.

Wrapping It Up

The short story says “Shakespeare invented 1,700 words.” The fuller picture reveals someone whose plays gave us hundreds of documented headwords and thousands of senses, counts that shift as new evidence appears.

More than that, his body of work offered a public stage for language to flourish – forms that were read, heard, printed, quoted, and imitated.

If we chase shorthand truths, “1,700 words, “we miss the thrill of how living language works, evolves – and how one writer’s boldness, paired with printing and performance, helped embed fresh expressions in the hearts and pages of English speakers for centuries.

So yes, Shakespeare helped give us heaps of words that still sound perfectly natural today. Exactly how many? That depends on who’s checking – and when.

If you’re a true admirer of Shakespeare and his timeless works, you won’t want to miss the festivals across the US that celebrate his genius!